CHARACTER DESIGN • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• CHARLES NORTON:

As with all of the Doctor Who (and Dad's Army) animations so far produced at BBC Studios, our character artist on The Macra Terror was Martin Geraghty. He joined us on the production toward the end of March 2018, kicking off with some redrafting work on the character of Ben - a character we'd worked with before, but had never been entirely happy with. For the character of the Doctor (Patrick Troughton) we reused line-work we already had on file from the last time we animated him. There followed a period of a few weeks before Martin was able to join the crew fully, as he'd also been booked to draw a comic strip for Doctor Who Magazine. However, when work on the strip was completed, principal character design was able to begin properly from around the end of May - starting with an ambitious redesign of the titular Macra monster itself.

• MARTIN GERAGHTY:

I was initially approached by Charles and Paul to provide the character designs for The Macra Terror animation not long after I’d finished Shada, and I was obviously delighted that my previous partners in crime, Adrian, Rob and (background artists) Graham Bleathman and Colin Howard were all onboard too.

My approach to the comic strips and to the animation projects is surprisingly different, when looked at objectively. The strip is obviously more akin to the storyboards (that were wonderfully brought to life by Adrian on The Macra Terror). The strip allows for more detail to be brought to the characters, as well as being able to work ‘in the round’ as it were. Animation is quite different. Except for some specific poses that are checked off later in the character design process (i.e. people on the floor; or crouching; or maybe some high overhead shots), the animated characters generally have to be constructed at a standard eye-level within the screen. Therefore some extreme angles, often noticeable on the tele-snaps, have to be excluded in order to reduce later animation work and to meet the timescale allowed.

Also, in comics, the artist generally constructs the sets, locations, clothing and lighting of the story that they’re illustrating. With the animation, it’s much later in the scheme of things that I’ll get to see how my animated characters are interacting in the environment created by the other members of the backgrounds team - Colin, Graham, Lydia and Rob.

• CHARLES NORTON:

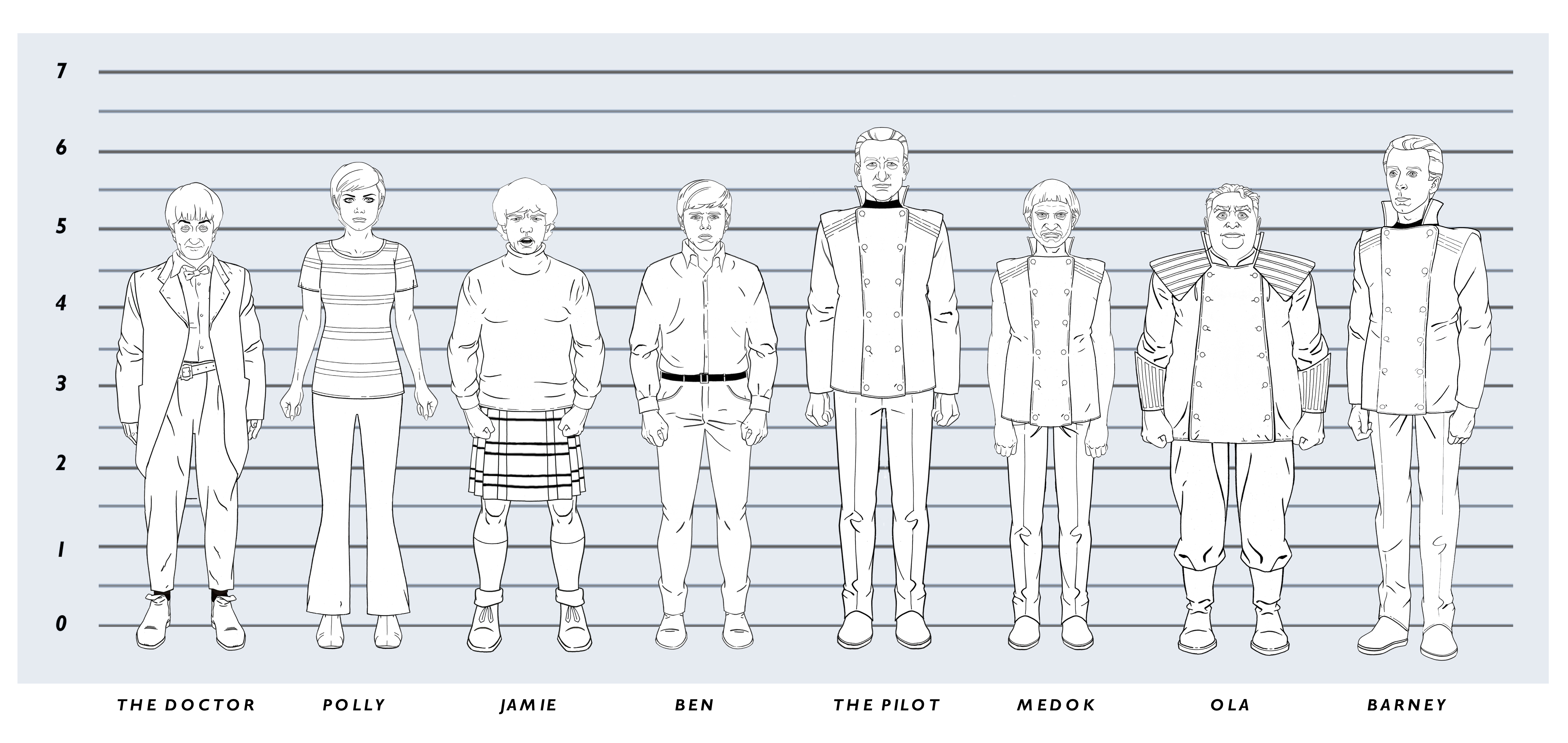

There are some 24 core characters in The Macra Terror, not including maybe a dozen or so non-speaking background characters. With only a finite amount of time and only the one character artist, several practical workarounds needed to be developed to make this massive workload practical with the resources available.

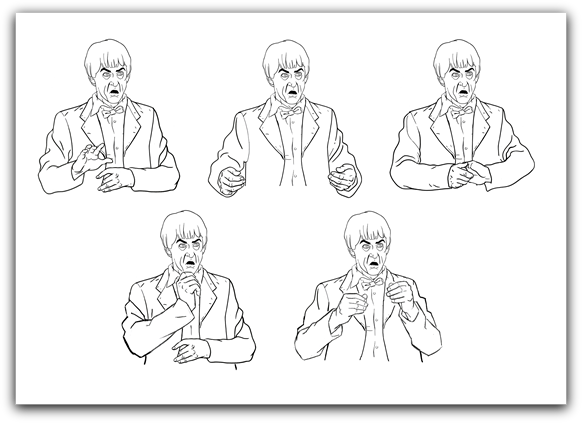

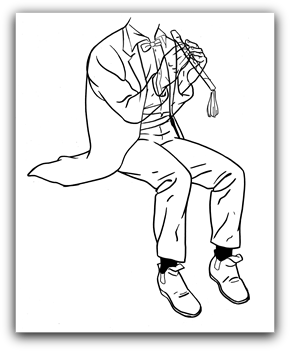

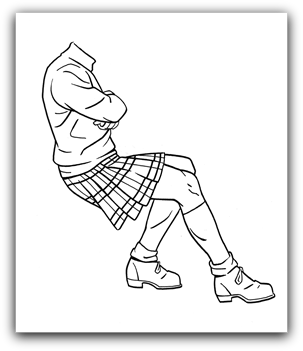

In animation, it is normal for a basic character to be drawn from a bare minimum of five different angles:

1. Looking dead ahead - facing forward.

2. Looking off at a forward facing three-quarter angle.

3. In perfect side-on profile.

4. At a backward facing three-quarter angle, looking away from us.

5. A perfect rear view of the back of their head, facing flat away from us.

That's the basic turnaround. Of course, for some characters, you'll need more than that. Sometimes, a lot more. I think there's a basic kit of about nine angles for the Doctor, for instance. Some less important characters meanwhile can be pared down to just three or four angles.

• CHARLES NORTON:

As with all of the Doctor Who (and Dad's Army) animations so far produced at BBC Studios, our character artist on The Macra Terror was Martin Geraghty. He joined us on the production toward the end of March 2018, kicking off with some redrafting work on the character of Ben - a character we'd worked with before, but had never been entirely happy with. For the character of the Doctor (Patrick Troughton) we reused line-work we already had on file from the last time we animated him. There followed a period of a few weeks before Martin was able to join the crew fully, as he'd also been booked to draw a comic strip for Doctor Who Magazine. However, when work on the strip was completed, principal character design was able to begin properly from around the end of May - starting with an ambitious redesign of the titular Macra monster itself.

• MARTIN GERAGHTY:

I was initially approached by Charles and Paul to provide the character designs for The Macra Terror animation not long after I’d finished Shada, and I was obviously delighted that my previous partners in crime, Adrian, Rob and (background artists) Graham Bleathman and Colin Howard were all onboard too.

My approach to the comic strips and to the animation projects is surprisingly different, when looked at objectively. The strip is obviously more akin to the storyboards (that were wonderfully brought to life by Adrian on The Macra Terror). The strip allows for more detail to be brought to the characters, as well as being able to work ‘in the round’ as it were. Animation is quite different. Except for some specific poses that are checked off later in the character design process (i.e. people on the floor; or crouching; or maybe some high overhead shots), the animated characters generally have to be constructed at a standard eye-level within the screen. Therefore some extreme angles, often noticeable on the tele-snaps, have to be excluded in order to reduce later animation work and to meet the timescale allowed.

Also, in comics, the artist generally constructs the sets, locations, clothing and lighting of the story that they’re illustrating. With the animation, it’s much later in the scheme of things that I’ll get to see how my animated characters are interacting in the environment created by the other members of the backgrounds team - Colin, Graham, Lydia and Rob.

• CHARLES NORTON:

There are some 24 core characters in The Macra Terror, not including maybe a dozen or so non-speaking background characters. With only a finite amount of time and only the one character artist, several practical workarounds needed to be developed to make this massive workload practical with the resources available.

In animation, it is normal for a basic character to be drawn from a bare minimum of five different angles:

1. Looking dead ahead - facing forward.

2. Looking off at a forward facing three-quarter angle.

3. In perfect side-on profile.

4. At a backward facing three-quarter angle, looking away from us.

5. A perfect rear view of the back of their head, facing flat away from us.

That's the basic turnaround. Of course, for some characters, you'll need more than that. Sometimes, a lot more. I think there's a basic kit of about nine angles for the Doctor, for instance. Some less important characters meanwhile can be pared down to just three or four angles.

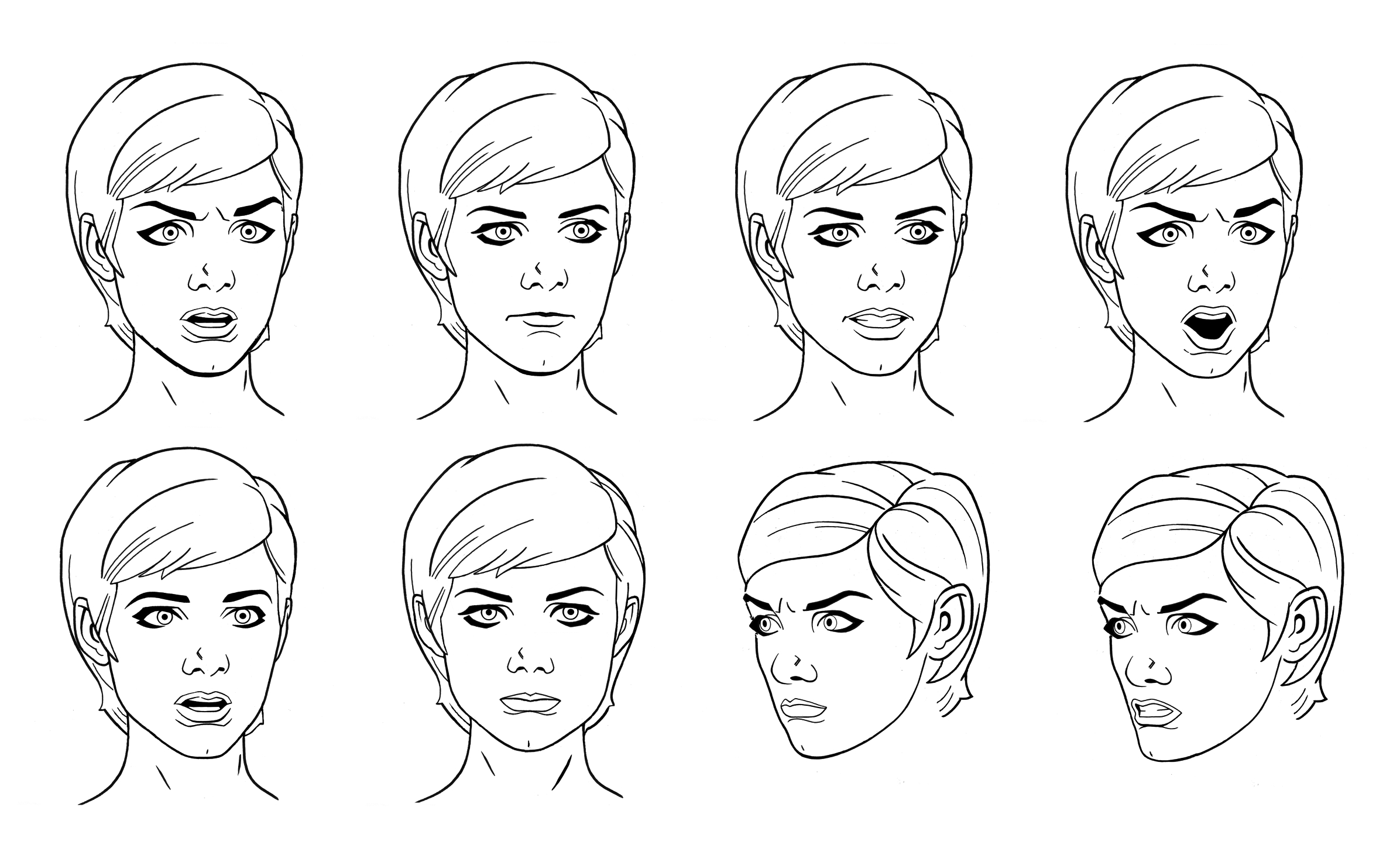

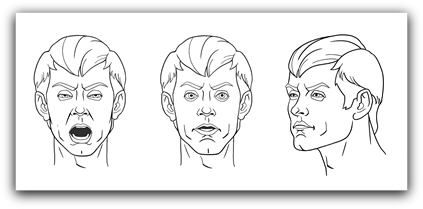

Once you have a design from all the basic angles, you then need multiple poses for the arms and legs. And after that, various layers on top of the artwork to show all the different parts of their face and body. This is where the number of drawings can really start to stack up as you need many different facial expressions for every angle of a character's face. You can quickly appreciate the colossal workload involved. And on small budget productions like this, we only have the one character artist - Martin. So that's one man, drawing every character, multiple times, with multiple expressions and in multiple poses. Every hand shape and every eye-brow. Every smile and every shout. During the course of everyday conversation, an average person will display an extraordinary array of different facial expressions and they all have to be drawn.

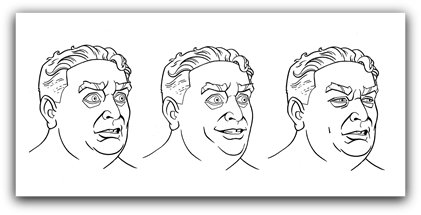

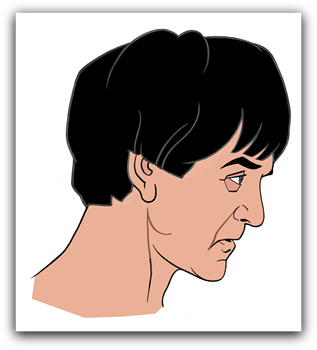

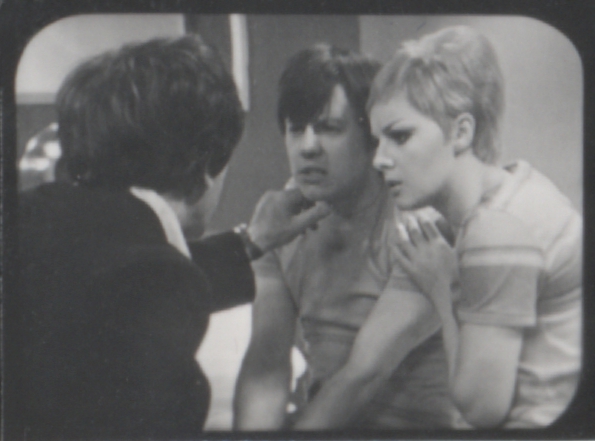

The mouth is an especially busy area, due to lip-sync. The human mouth does a number of very precise things when forming speech. For instance, when you make an 'O' sound, your mouth takes on a rounded shape, with a lot of height between the upper and lower lip. When you make an 'EE' sound, the mouth gets wider and taught. Any 'B' or 'P' sounds push the lower lip out to make a plosive. Every single syllable in every single word creates a slightly different mouth shape. And just to make life more difficult, every single person forms these shapes differently. It's as unique as a fingerprint and it defines the personalities of the actors. To look at the actors in The Macra Terror, Patrick Troughton tends to talk slightly out of the side of his mouth and displays a noticeable gap in his teeth. Anneke Wills' character meanwhile pulls the edges of her mouth back quite wide when displaying fear. Frazer Hines is particularly interesting because he has very full lips, with his character barely ever having his mouth completely closed.

The mouth is an especially busy area, due to lip-sync. The human mouth does a number of very precise things when forming speech. For instance, when you make an 'O' sound, your mouth takes on a rounded shape, with a lot of height between the upper and lower lip. When you make an 'EE' sound, the mouth gets wider and taught. Any 'B' or 'P' sounds push the lower lip out to make a plosive. Every single syllable in every single word creates a slightly different mouth shape. And just to make life more difficult, every single person forms these shapes differently. It's as unique as a fingerprint and it defines the personalities of the actors. To look at the actors in The Macra Terror, Patrick Troughton tends to talk slightly out of the side of his mouth and displays a noticeable gap in his teeth. Anneke Wills' character meanwhile pulls the edges of her mouth back quite wide when displaying fear. Frazer Hines is particularly interesting because he has very full lips, with his character barely ever having his mouth completely closed.

They say that for an average character you can rationalise these mouth shapes down to about ten basic variations. This covers most of the conversational word sounds. Add to that a handful of basic eye-brow positions too. So, with an average of five heads per character, that works out at around 65 component drawings per character's head (plus a base neutral head). On top of that there's also all those other little quirky expressions that helps define each person - winks, twitches, squints and subtle half-smiles. We map all these out on increasingly complex character grids, which Martin patiently goes through and draws up for us - first in pencil and then over the top with a fine ink-layer, before scanning in and sending down the line to either Adrian (for colour work) or to me to pass onto the studio. And again, just to hammer the point home - Martin is doing all of this solo.

• MARTIN GERAGHTY:

Simplifying the performers involved is key. Excess line work in the character of a face really has to be pared right down to allow the animators to work as economically and fluidly as possible. Troughton has a jowly, hang-dog face that is a joy to transform into pencil, but in animation you have to rely on the studio more to tease his idiosyncratic performance to the screen.

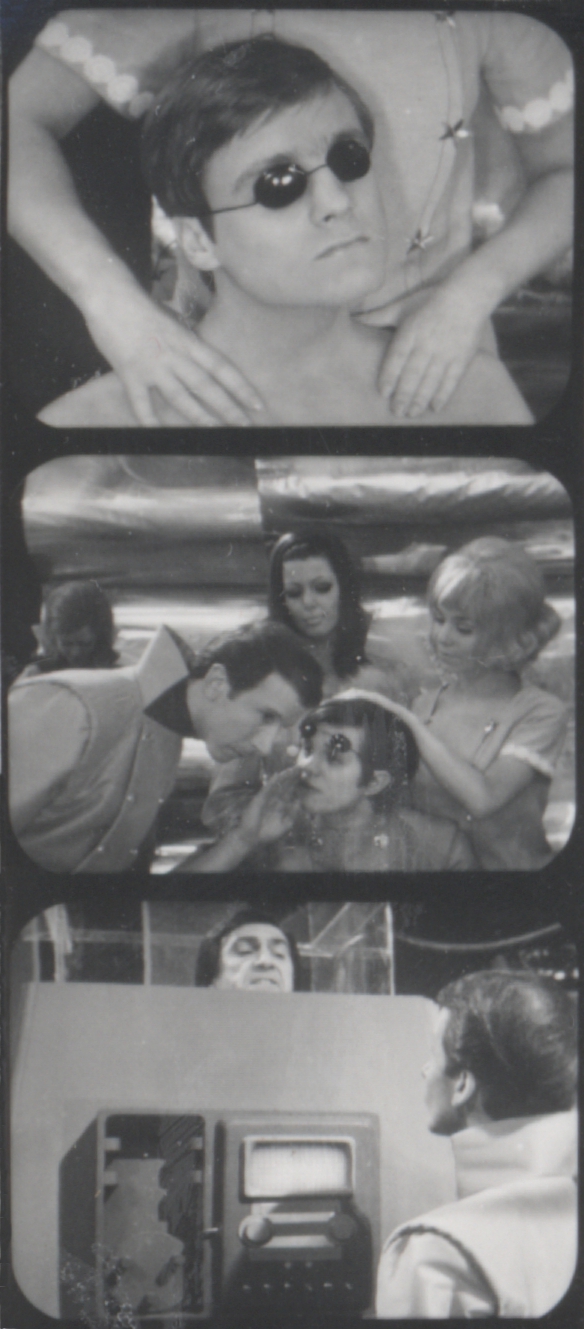

This particular TARDIS team, with the exception of Jamie, had already been animated in our previous production of The Power of the Daleks, but what the core team experienced on that first ‘baptism of fire’ dictated that we revisit the leads for this production. That was one of the first issues we addressed, mostly with a considerable degree of success, I feel. Although, the later translation of those drawings by the studio, did occasionally lead to the characters sometimes going 'off-model'. The most noticeable case being the likeness of Polly - something that has been pointed out to me, with her typical sense of mischief, by Anneke Wills herself! This is an inevitable drawback of the conveyor-belt process, as various artists bring their own sets of skills to an evolving design.

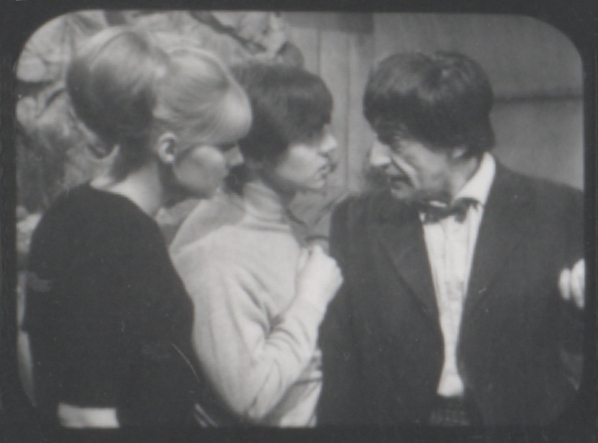

Popular character actors of the era, such as Peter Jeffrey and Gertan Klauber are obviously, a joy to tackle. However, performers with a lower profile can be a more difficult proposition and often it’s necessary to cast the net a little wider to find decent visual reference. Outside of a low resolution tele-snap, they often have a very small footprint on Google images. In these instances, we sometimes have to find photographs of the actors later in life, appearing in TV shows from the 1970s and 1980s and then ‘de-age’ them in the drawing process - bringing them more in line with their 1960s selves.

Simplifying the performers involved is key. Excess line work in the character of a face really has to be pared right down to allow the animators to work as economically and fluidly as possible. Troughton has a jowly, hang-dog face that is a joy to transform into pencil, but in animation you have to rely on the studio more to tease his idiosyncratic performance to the screen.

This particular TARDIS team, with the exception of Jamie, had already been animated in our previous production of The Power of the Daleks, but what the core team experienced on that first ‘baptism of fire’ dictated that we revisit the leads for this production. That was one of the first issues we addressed, mostly with a considerable degree of success, I feel. Although, the later translation of those drawings by the studio, did occasionally lead to the characters sometimes going 'off-model'. The most noticeable case being the likeness of Polly - something that has been pointed out to me, with her typical sense of mischief, by Anneke Wills herself! This is an inevitable drawback of the conveyor-belt process, as various artists bring their own sets of skills to an evolving design.

Popular character actors of the era, such as Peter Jeffrey and Gertan Klauber are obviously, a joy to tackle. However, performers with a lower profile can be a more difficult proposition and often it’s necessary to cast the net a little wider to find decent visual reference. Outside of a low resolution tele-snap, they often have a very small footprint on Google images. In these instances, we sometimes have to find photographs of the actors later in life, appearing in TV shows from the 1970s and 1980s and then ‘de-age’ them in the drawing process - bringing them more in line with their 1960s selves.

• CHARLES NORTON:

Martin refers to The Power of the Daleks as a ‘baptism of fire’. Just to explain, the project was really hindered by a lack of both time, and to a lesser extent, money. Those limitations dictated everything we did on it. So, for example, we had to embed all the shading into the character kits, as there was no time to animate the shadows in a second pass. We had to avoid head-turns, as they would take a long time to render convincingly. We also had to rush. A lot. Quite often, if something didn't quite work first time round, there was no option to revisit it with a second pass. It just had to go out as it was. I know Martin was very unhappy with how Ben turned out and I agreed with most of his criticisms of the final kit, but there was no time to do any more with the character on Power. We just had to press on and rig the character as he was. When The Macra Terror rolled around, it afforded Martin the chance to dive back into both Ben and Polly and have a tinker with the line-work. Something, I know he was very keen to do.

EDITING • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• CHARLES NORTON:

Working with a limited budget, you have to manage your resources very carefully. Without the money to pay for a huge team of artists and with our attempts at cloning Martin having thus far proved unsuccessful, you do eventually reach a point where you need to start managing the workload somewhat. Otherwise there's no practical way to get through it all in time.

On The Macra Terror, the biggest economies that we made were to do with hair and costume. In the original 1967 production of the story, the lead characters shuttle through a number of different costume changes and hairstyles in quite a short time. And, as discussed above, each one of these costumes and hairstyles needs to be drawn multiple times from multiple different angles - all by hand. And that's before you get started on the task of keeping track of them all across the production and making sure the right person is wearing the right thing in the right scene. Does this scene feature Jamie in his first Episode 1 costume or his second? Or is he into his Episode 2 costume, which he changes out of before the final scene of Episode 4? You can imagine the spreadsheets involved!

Martin refers to The Power of the Daleks as a ‘baptism of fire’. Just to explain, the project was really hindered by a lack of both time, and to a lesser extent, money. Those limitations dictated everything we did on it. So, for example, we had to embed all the shading into the character kits, as there was no time to animate the shadows in a second pass. We had to avoid head-turns, as they would take a long time to render convincingly. We also had to rush. A lot. Quite often, if something didn't quite work first time round, there was no option to revisit it with a second pass. It just had to go out as it was. I know Martin was very unhappy with how Ben turned out and I agreed with most of his criticisms of the final kit, but there was no time to do any more with the character on Power. We just had to press on and rig the character as he was. When The Macra Terror rolled around, it afforded Martin the chance to dive back into both Ben and Polly and have a tinker with the line-work. Something, I know he was very keen to do.

EDITING • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• CHARLES NORTON:

Working with a limited budget, you have to manage your resources very carefully. Without the money to pay for a huge team of artists and with our attempts at cloning Martin having thus far proved unsuccessful, you do eventually reach a point where you need to start managing the workload somewhat. Otherwise there's no practical way to get through it all in time.

On The Macra Terror, the biggest economies that we made were to do with hair and costume. In the original 1967 production of the story, the lead characters shuttle through a number of different costume changes and hairstyles in quite a short time. And, as discussed above, each one of these costumes and hairstyles needs to be drawn multiple times from multiple different angles - all by hand. And that's before you get started on the task of keeping track of them all across the production and making sure the right person is wearing the right thing in the right scene. Does this scene feature Jamie in his first Episode 1 costume or his second? Or is he into his Episode 2 costume, which he changes out of before the final scene of Episode 4? You can imagine the spreadsheets involved!

• MARTIN GERAGHTY:

Simplification is a requirement with all the characters. You are tasked with pulling out the facial characteristics of these actors - prominent noses, gapped teeth, gimlet eyes, etc. Not quite true to life but caricatured enough so they don’t stray too far into Captain Pugwash territory.

Luckily, apart from the regulars, most of the characters in this story wear similar 1960s science-fiction clothing, which is a godsend in jobs such as this one. The same body model can then be used multiple times, albeit with tweaks applied in Photoshop to alter the height and width.

• CHARLES NORTON:

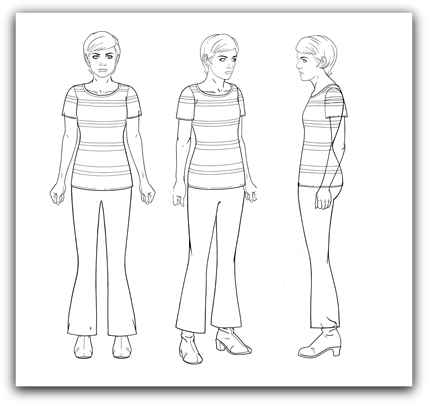

Simplifications happen. They always do in animation. The best example of this on The Macra Terror is probably the character of Polly. In the original 1967 production, Polly starts off wearing a dark T-shirt and light trousers. She has very long hair, bunched up at the back in a thick pony-tail. This is a change from how she appeared at the end of the previous story by the way, where she wore a space-suit. About halfway through the first episode of The Macra Terror, Polly then (somewhat oddly) goes to a beauty salon. It is there that she appears to have a hair-cut. She spends the rest of the episode with short hair (which was a wig, by the way). She also spends the rest of Episode 1 wearing a dark double-breasted tunic with square-cut neckline. We next catch up with her in Episode 2, but now, Polly now looks very different. She still has short hair, but it's styled a bit differently to how it was at the end of the previous episode, even though the events in Episode 2 take place mere hours after the events in Episode 1. And most strangely of all, Polly is now wearing a new striped T-shirt that she definitely didn't have at any point during the previous episode. Where did it come from? It's never explained.

Simplification is a requirement with all the characters. You are tasked with pulling out the facial characteristics of these actors - prominent noses, gapped teeth, gimlet eyes, etc. Not quite true to life but caricatured enough so they don’t stray too far into Captain Pugwash territory.

Luckily, apart from the regulars, most of the characters in this story wear similar 1960s science-fiction clothing, which is a godsend in jobs such as this one. The same body model can then be used multiple times, albeit with tweaks applied in Photoshop to alter the height and width.

• CHARLES NORTON:

Simplifications happen. They always do in animation. The best example of this on The Macra Terror is probably the character of Polly. In the original 1967 production, Polly starts off wearing a dark T-shirt and light trousers. She has very long hair, bunched up at the back in a thick pony-tail. This is a change from how she appeared at the end of the previous story by the way, where she wore a space-suit. About halfway through the first episode of The Macra Terror, Polly then (somewhat oddly) goes to a beauty salon. It is there that she appears to have a hair-cut. She spends the rest of the episode with short hair (which was a wig, by the way). She also spends the rest of Episode 1 wearing a dark double-breasted tunic with square-cut neckline. We next catch up with her in Episode 2, but now, Polly now looks very different. She still has short hair, but it's styled a bit differently to how it was at the end of the previous episode, even though the events in Episode 2 take place mere hours after the events in Episode 1. And most strangely of all, Polly is now wearing a new striped T-shirt that she definitely didn't have at any point during the previous episode. Where did it come from? It's never explained.

There were similar problems with a number of the characters in The Macra Terror. The solution was to go through each character in turn and simplify the number of costume changes. This would not only make Martin's workload more manageable, but it would also help to eliminate the odd in-story continuity error as well. As a result, in our finished animation, Polly stays in her striped T-shirt throughout the whole story and her hair remains one consistent length. As it was effectively a new production and we weren't having to slot in with anything else, we only really needed to make the continuity work within the story we were telling.

Of course, making these kind of practical changes can have knock-on effects elsewhere. Changing Polly's hair meant that we had to shorten one scene in the first episode, in order to remove a section of dialogue in which Polly actually discusses having her hair done. But there were other aspects of the scene that presented their own issues as well.

As it was, leaving the scene uncut would have meant creating a number of completely new characters specifically for that one sequence. These extra characters would have taken a long time to fully draw up and Martin was already working flat-out as it was. In the end, we only just had enough time (and energy) to get all the core cast characters completed without throwing in additional ones. On top of this, there's the not inconsiderable challenge of actually animating someone having their hair washed and cut, with a sink and running water. This would have been yet another big job. Although it's not the aspect fans tend to flag up afterwards, Polly having her hair done was the main stumbling block with this scene. The Doctor's turn in the rough-and-tumble machine (which also appeared in that sequence) would have certainly also added to the workload. However, that part of the scene was more collateral damage than the main purpose of the editing. If you edit out all the stuff in which Polly has her hair cut, a lot of other bits of the scene also really need to go, otherwise you end up with a choppy mess of an edit. We kept as much of the scene as we possibly could without it sounding strange and nonsensical. Not that the rough and tumble machine wasn't also a problem on its own of course. The machine itself would have been another thing that Rob and the backgrounds team would have had to tackle and they were flat out too, but it was always the stuff with Polly's hair that was the bigger issue here and as such, it became an obvious cut to make.

• MARTIN GERAGHTY:

After the full set of characters were completed, we moved onto the specific poses that would be needed such as Medok in the interrogation chair; the Pilot leaning over his desk answering Ola’s message or Ben crouching on an overhead gantry. On several occasions these specific shots required later overdrawing and shading, after the studio's part of the animation had been completed, in order to fully implement the originating team’s vision.

Of course, making these kind of practical changes can have knock-on effects elsewhere. Changing Polly's hair meant that we had to shorten one scene in the first episode, in order to remove a section of dialogue in which Polly actually discusses having her hair done. But there were other aspects of the scene that presented their own issues as well.

As it was, leaving the scene uncut would have meant creating a number of completely new characters specifically for that one sequence. These extra characters would have taken a long time to fully draw up and Martin was already working flat-out as it was. In the end, we only just had enough time (and energy) to get all the core cast characters completed without throwing in additional ones. On top of this, there's the not inconsiderable challenge of actually animating someone having their hair washed and cut, with a sink and running water. This would have been yet another big job. Although it's not the aspect fans tend to flag up afterwards, Polly having her hair done was the main stumbling block with this scene. The Doctor's turn in the rough-and-tumble machine (which also appeared in that sequence) would have certainly also added to the workload. However, that part of the scene was more collateral damage than the main purpose of the editing. If you edit out all the stuff in which Polly has her hair cut, a lot of other bits of the scene also really need to go, otherwise you end up with a choppy mess of an edit. We kept as much of the scene as we possibly could without it sounding strange and nonsensical. Not that the rough and tumble machine wasn't also a problem on its own of course. The machine itself would have been another thing that Rob and the backgrounds team would have had to tackle and they were flat out too, but it was always the stuff with Polly's hair that was the bigger issue here and as such, it became an obvious cut to make.

• MARTIN GERAGHTY:

After the full set of characters were completed, we moved onto the specific poses that would be needed such as Medok in the interrogation chair; the Pilot leaning over his desk answering Ola’s message or Ben crouching on an overhead gantry. On several occasions these specific shots required later overdrawing and shading, after the studio's part of the animation had been completed, in order to fully implement the originating team’s vision.

ANAMATICS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• CHARLES NORTON:

An animatic (or a Leica reel, if you prefer) is a very important stage in the creation of an animation. It's the moment where your storyboard drawings are married up to the audio of the programme. The moment where those storyboards go from a sheet of paper to an actual bit of footage. This is when you decide on the timing of shot changes - the kind of camera moves you want and generally how you want to cut the whole thing together. Effectively, it's where you lock a full edit of the entire programme.

The first online edit for the animatics of The Macra Terror (Episodes 1 and 4) was conducted on 24th July, with BBC Studios' staff editor Johnathan Ogle in Edit Suite 3 located deep in the bowels of Television Centre. We'd just finished working with Johnny on preparing the broadcast master of Shada for BBC America a few days earlier and were back in the same room once again for The Macra Terror. I'd been working away at home on both a paper edit and an offline edit, but there really isn't any replacement for actually sitting down and doing the final fine cut in a full edit suite.

We continued with another edit day (on the animatic of Episode 2 and the remaining parts of Episode 4) on 6th August. With so much work to do on the animatic, I also edited some pretty large chunks of the last two episodes on my laptop at home and even 'borrowed' some edit time from a Dad's Army DVD that we were also working on at the time to give us a few more hours editing on Episode 4, again all at Television Centre.

While we were editing the animatics on Episodes 1, 2 and 4, Adrian was still working on the storyboards for Episode 3. However, it wasn't long before they too were complete and we could get back into the edit suite one last time to lock Episode 3 as well.

That final edit was completed on 12th September, back in Edit Suite 3, where we dropped in all of Adrian Salmon's boards for Episode 3. Adrian joined us for the edit that day and brought his pencils as well, so we could get any last minute sections we needed drawn up as we went along.

• ADRIAN SALMON:

I arrived at Television Centre around noon to find Charles and Johnny already deeply into the edit of Episode 3. I was there to help if I could, but mostly to see how my storyboards came together when finally married to the audio soundtrack. Scenes were replayed and beats adjusted and replayed again, as the animatic began to take shape.

My overriding concern was that there might not be enough material to fill the time of Jamie wandering lost through the old mine system. As a precaution I’d brought along drawing materials in case I needed to knock out some last minute artwork to patch any holes in the narrative.

I had forgotten to include drawings of Officia handing over a clipboard to the Doctor in one scene, so whilst the edit preceded with a different sequence, I sat somewhat cramped in the corner of the edit suite, frantically drawing a succession of new frames to be scanned and imported into the animatic.

Towards the end of the session, Charles had to nip out to talk with Paul Hembury, who’d popped his head in to see how things were going. Whilst they were gone I got the chance to direct a tiny bit of the edit myself, of Pilot talking to Ben, which was a satisfying conclusion to the day. We completed the edit on time and whilst I headed back to Euston station, I left Charles alone in the edit suite, working through the mass of emails that had piled up throughout the day.

BACKGROUND PAINTING • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• CHARLES NORTON:

With the large number of background elements needed, we brought three artists on board for The Macra Terror and spread the workload between them. A big change from our earliest projects, on which one artist painted literally everything. As usual, all of our 3D work and compositing would be handled by Rob Ritchie. We did have a back-up compositor waiting in the wings if needed, but in the end this wasn't required and Rob managed to do the whole lot. Somehow.

Of course, a potential problem in having more than one artist working on the backgrounds, is inconsistency. The end product should all ideally fit together as one cohesive whole, presenting the illusion of one artist's hand at work throughout. What you don't want is one scene painted in one artist's style and then another scene painted in a completely different style.

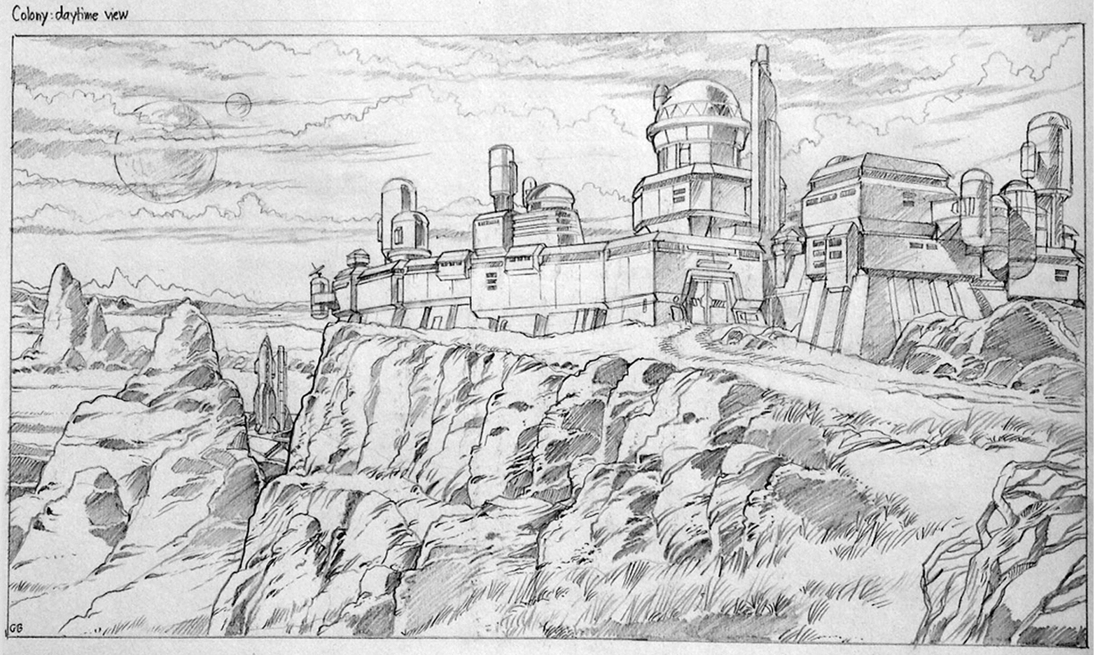

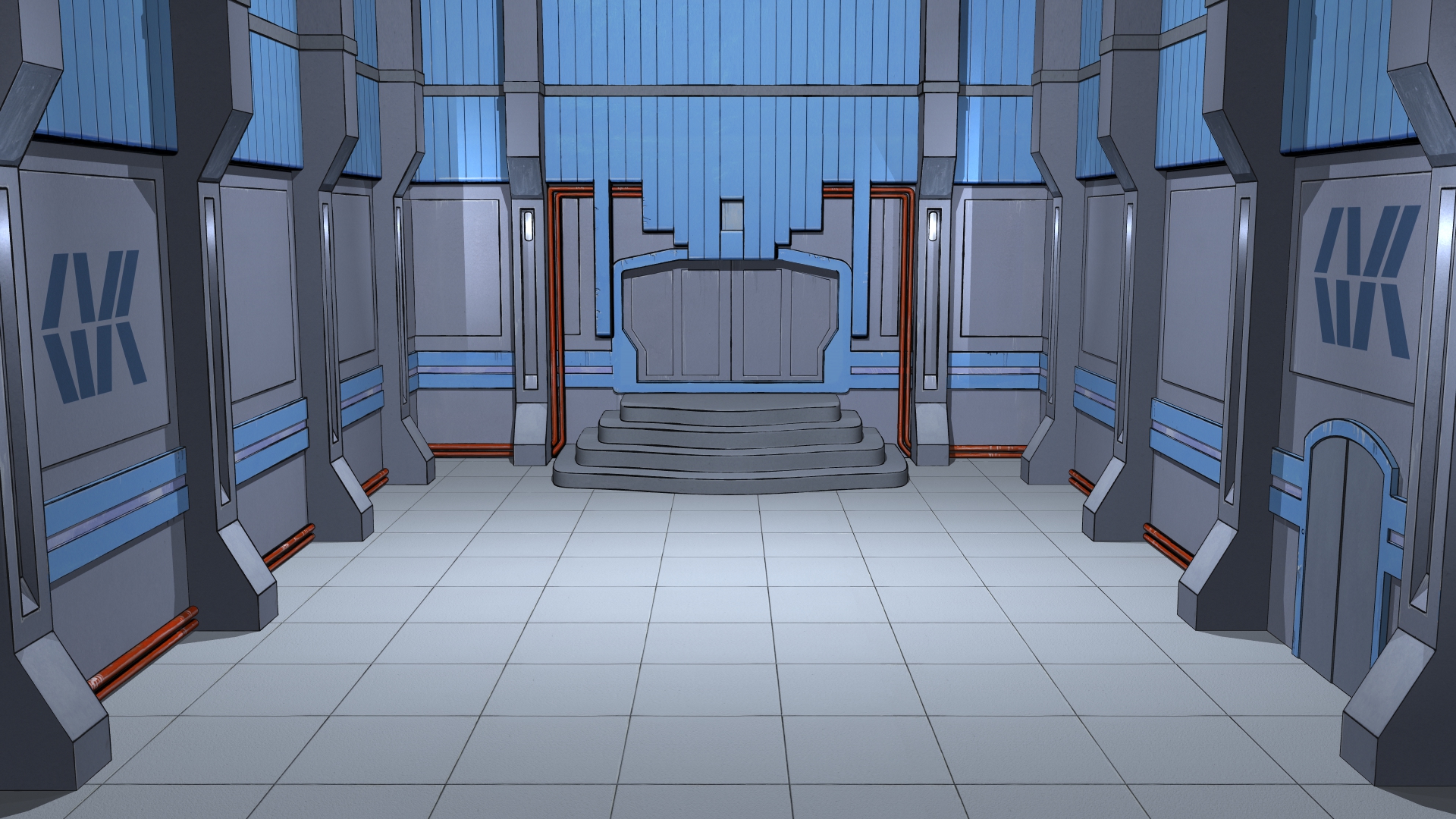

To avoid the risk of this happening, the background elements were divided up between the artists very carefully. Broadly speaking, anything featuring the main living areas of the colony itself, with its big halls, towers and courtyards would be handled by Graham Bleathman, with whom we'd worked recently on Shada. Graham works a lot in gouache paint and I felt his past experience on things like Dan Dare and Thunderbirds would be a good fit for the colony's projection of a futurist utopia.

• CHARLES NORTON:

An animatic (or a Leica reel, if you prefer) is a very important stage in the creation of an animation. It's the moment where your storyboard drawings are married up to the audio of the programme. The moment where those storyboards go from a sheet of paper to an actual bit of footage. This is when you decide on the timing of shot changes - the kind of camera moves you want and generally how you want to cut the whole thing together. Effectively, it's where you lock a full edit of the entire programme.

The first online edit for the animatics of The Macra Terror (Episodes 1 and 4) was conducted on 24th July, with BBC Studios' staff editor Johnathan Ogle in Edit Suite 3 located deep in the bowels of Television Centre. We'd just finished working with Johnny on preparing the broadcast master of Shada for BBC America a few days earlier and were back in the same room once again for The Macra Terror. I'd been working away at home on both a paper edit and an offline edit, but there really isn't any replacement for actually sitting down and doing the final fine cut in a full edit suite.

We continued with another edit day (on the animatic of Episode 2 and the remaining parts of Episode 4) on 6th August. With so much work to do on the animatic, I also edited some pretty large chunks of the last two episodes on my laptop at home and even 'borrowed' some edit time from a Dad's Army DVD that we were also working on at the time to give us a few more hours editing on Episode 4, again all at Television Centre.

While we were editing the animatics on Episodes 1, 2 and 4, Adrian was still working on the storyboards for Episode 3. However, it wasn't long before they too were complete and we could get back into the edit suite one last time to lock Episode 3 as well.

That final edit was completed on 12th September, back in Edit Suite 3, where we dropped in all of Adrian Salmon's boards for Episode 3. Adrian joined us for the edit that day and brought his pencils as well, so we could get any last minute sections we needed drawn up as we went along.

• ADRIAN SALMON:

I arrived at Television Centre around noon to find Charles and Johnny already deeply into the edit of Episode 3. I was there to help if I could, but mostly to see how my storyboards came together when finally married to the audio soundtrack. Scenes were replayed and beats adjusted and replayed again, as the animatic began to take shape.

My overriding concern was that there might not be enough material to fill the time of Jamie wandering lost through the old mine system. As a precaution I’d brought along drawing materials in case I needed to knock out some last minute artwork to patch any holes in the narrative.

I had forgotten to include drawings of Officia handing over a clipboard to the Doctor in one scene, so whilst the edit preceded with a different sequence, I sat somewhat cramped in the corner of the edit suite, frantically drawing a succession of new frames to be scanned and imported into the animatic.

Towards the end of the session, Charles had to nip out to talk with Paul Hembury, who’d popped his head in to see how things were going. Whilst they were gone I got the chance to direct a tiny bit of the edit myself, of Pilot talking to Ben, which was a satisfying conclusion to the day. We completed the edit on time and whilst I headed back to Euston station, I left Charles alone in the edit suite, working through the mass of emails that had piled up throughout the day.

BACKGROUND PAINTING • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• CHARLES NORTON:

With the large number of background elements needed, we brought three artists on board for The Macra Terror and spread the workload between them. A big change from our earliest projects, on which one artist painted literally everything. As usual, all of our 3D work and compositing would be handled by Rob Ritchie. We did have a back-up compositor waiting in the wings if needed, but in the end this wasn't required and Rob managed to do the whole lot. Somehow.

Of course, a potential problem in having more than one artist working on the backgrounds, is inconsistency. The end product should all ideally fit together as one cohesive whole, presenting the illusion of one artist's hand at work throughout. What you don't want is one scene painted in one artist's style and then another scene painted in a completely different style.

To avoid the risk of this happening, the background elements were divided up between the artists very carefully. Broadly speaking, anything featuring the main living areas of the colony itself, with its big halls, towers and courtyards would be handled by Graham Bleathman, with whom we'd worked recently on Shada. Graham works a lot in gouache paint and I felt his past experience on things like Dan Dare and Thunderbirds would be a good fit for the colony's projection of a futurist utopia.

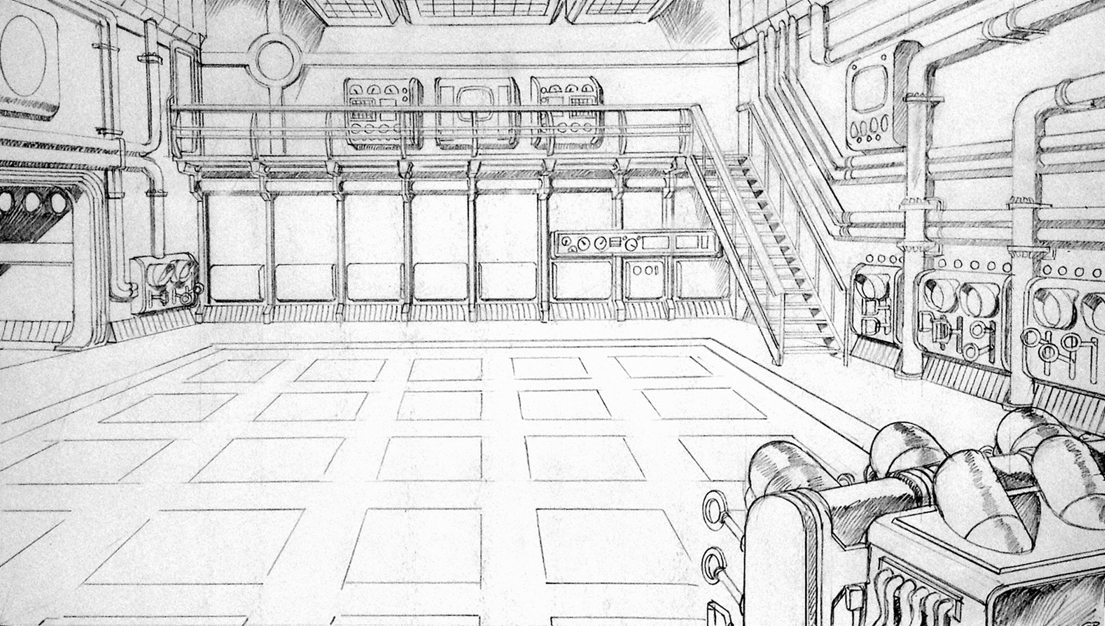

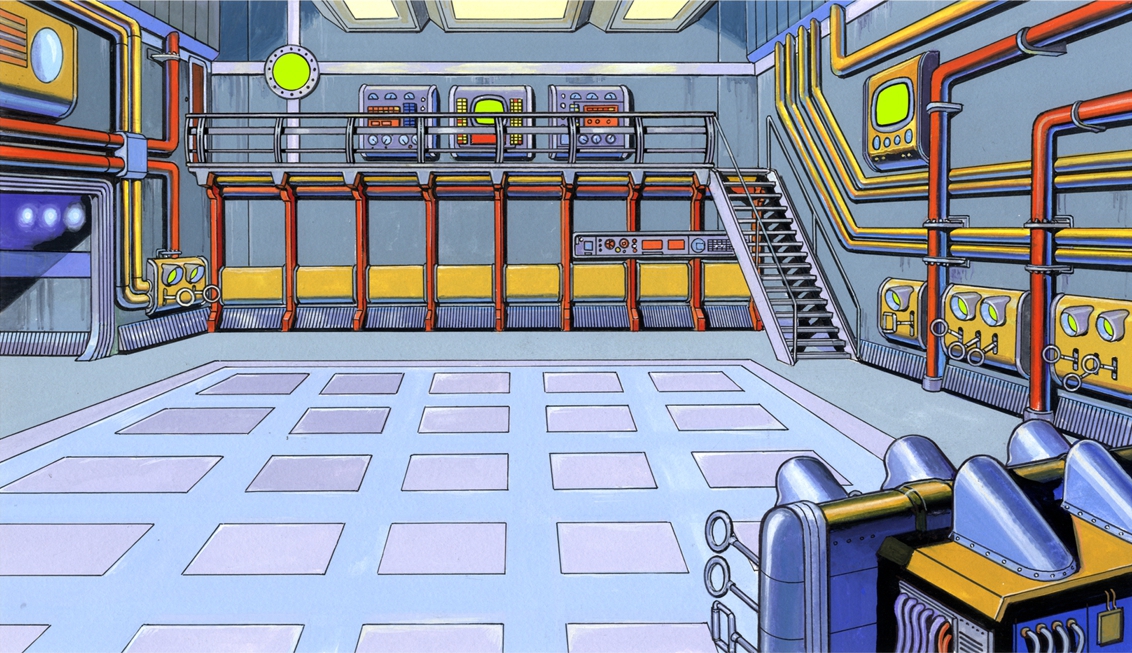

The background paintings themselves were essentially split into two basic types. Some were conventional locked background plates - perhaps painted with layered sections, but essentially providing a single locked view in perspective. Examples of this would include the shot in Episode 4 where two characters cross over a metal walkway and also the establishing shots of the colony exterior. However, for some sets, there were simply too many different angles needed over the course of a scene for us to have every single shot painted out individually. In these cases, the solution was to use a kind of projection mapping that takes a flat painting of a single surface (perhaps of a wall) and then maps that flat wall onto one surface of a 3D modelled object in the computer. So, for a room with four interior walls, there would be four separate paintings, that would be each scanned into the computer from the physical paper or canvas and then mapped onto a basic 3D model of the interior of that room. Once you've done this, you effectively have a 3D model of the inside of that room, but every surface you look at is still a hand-painted image, with visible brush-strokes, physical paint flecks and paper texture intact. Although this technique is not often used in television animation, it's not a new idea. We actually nicked the entire concept from the 1998 Dreamworks film, Prince of Egypt which invented this way of building up backgrounds in the computer. It was later refined on films like Disney's Tarzan and The Princess and the Frog.

As with all the 3D modelling on The Macra Terror, the mapping work was all done by Rob Ritchie, who does a much better job of explaining this complex technique than I can...

• ROB RITCHIE:

Graham Bleathman was commissioned to create a series of flat wall sets that I would turn into full 3D models that could be digitally lit and rendered at any angle. This process involved taking the four walls that Graham had painted, stitching them together in Photoshop, making sure they all lined up. Using Lightwave 3D, I effectively traced the image using a selection of square and rectangular shapes, building outwards the geometry of the set. Once complete, this long wall was essentially folded four times to create a four-walled set.

As with all the 3D modelling on The Macra Terror, the mapping work was all done by Rob Ritchie, who does a much better job of explaining this complex technique than I can...

• ROB RITCHIE:

Graham Bleathman was commissioned to create a series of flat wall sets that I would turn into full 3D models that could be digitally lit and rendered at any angle. This process involved taking the four walls that Graham had painted, stitching them together in Photoshop, making sure they all lined up. Using Lightwave 3D, I effectively traced the image using a selection of square and rectangular shapes, building outwards the geometry of the set. Once complete, this long wall was essentially folded four times to create a four-walled set.

• CHARLES NORTON:

Much of the story of The Macra Terror takes place underground, especially in the last two episodes. When we get down into the tunnels with their dusty wooden roof-supports, cage-lifts and rusty mine-carts, the aesthetic of the backgrounds was always going need to be a little different. So, for these earthier more organic areas, I brought in Colin Howard with whom we'd worked on both The Power of the Daleks and Shada. Colin is rather in his element with all those dusty earth surfaces, craggy rocks and wood-grains. He also handled the TARDIS interior, as he'd previously done some work on the TARDIS for Shada, so there seemed to be a logical extension of that here.

Much of the story of The Macra Terror takes place underground, especially in the last two episodes. When we get down into the tunnels with their dusty wooden roof-supports, cage-lifts and rusty mine-carts, the aesthetic of the backgrounds was always going need to be a little different. So, for these earthier more organic areas, I brought in Colin Howard with whom we'd worked on both The Power of the Daleks and Shada. Colin is rather in his element with all those dusty earth surfaces, craggy rocks and wood-grains. He also handled the TARDIS interior, as he'd previously done some work on the TARDIS for Shada, so there seemed to be a logical extension of that here.

• COLIN HOWARD:

For this project I worked in acrylics, painting the background art directly over my initial scanned pencil art. I then used various synthetic brushes in varying sizes, working on multimedia cartridge paper, A3 and A4 in size. The final art was then scanned into the computer at a resolution of between 300 to 600 pixels.

My work on The Macra Terror begins with the opening scene of the TARDIS in orbit over the colony planet. For this scene I liased with the very talented Rob Ritchie whose 3D composites and lighting effects adorn these productions. I often supplied hand painted ‘wraps’ for 3D objects that he then rendered and placed ‘in shot’.

The planet in orbit consisted of half a 3D sphere that I supplied as a hand painted disc to wrap over the ‘Pangea-style’ land mass. The image was then dropped onto the sphere with the sea colour added beneath, I also supplied another digital cloud layer that could be rotated on top for a realistic look.

For this project I worked in acrylics, painting the background art directly over my initial scanned pencil art. I then used various synthetic brushes in varying sizes, working on multimedia cartridge paper, A3 and A4 in size. The final art was then scanned into the computer at a resolution of between 300 to 600 pixels.

My work on The Macra Terror begins with the opening scene of the TARDIS in orbit over the colony planet. For this scene I liased with the very talented Rob Ritchie whose 3D composites and lighting effects adorn these productions. I often supplied hand painted ‘wraps’ for 3D objects that he then rendered and placed ‘in shot’.

The planet in orbit consisted of half a 3D sphere that I supplied as a hand painted disc to wrap over the ‘Pangea-style’ land mass. The image was then dropped onto the sphere with the sea colour added beneath, I also supplied another digital cloud layer that could be rotated on top for a realistic look.

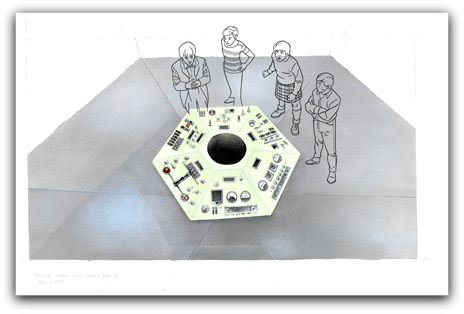

For the TARDIS interior, I was given a basic shot layout, in which the TARDIS crew would be standing behind the console viewed from above. This ended up being used for the DVD/Blu-ray menu screen. I decided that due to the angle involved, it would be a good idea to do this one as components, as the console room's roundels would pose quite a challenge at this angle when painted freehand. So the floor and console were on one piece of multimedia art paper with all the era-correct switches/controls positioned at that angle, but without the rotor. This would be added by Rob later, who would weave his digital wand to both illuminate it and make it move. I added shadow onto the floor and then separately painted some roundels in their ‘un-back-lit’ darker mode, as well as a wall section for Rob to utilise when building the room. Rob also added some lovely reflections of the walls on the floor when lighting that scene.

The TARDIS monitor screen is based on a version that originally appeared in the 1972 Doctor Who story, The Three Doctors. I supplied it as a ‘flat-wrap’ for Rob to put around the basic shape of the ceiling-mounted monitor along with the supports to connect it to the console room roof, which then comes to life when they get their first view the claw of the Macra. For these I have to think about the dimensions of the object and supply the detail for each surface where it folds up together to form the component, like a bizarre digital origami.

Medok's cell required several paintings of the same room at different angles. The first features the door, where the Doctor enters the cell. This included the steps down into the cell (which were made taller later on). So there was lots of wall texture required for this one. I decided to go for a traditional rough block wall to add to the bleakness of the room, with lots of lovely texture in the blocks.

The door was painted separately as well, to enable it to be easily cut out and animate it opening. I went initially for a wall entry/communicator panel system for security, as it’s a future colony, however as this was for a programme from the 1960s, the script required a traditional key entry system, so this was added to the image.

For the viewpoint showing the bench in the cell where the Doctor sits, I added a barred window for interest, as well as a few messages scratched into the wall by former inmates. We then realised I had to paint the same image from a different angle for when the Doctor kneels down to free Medok’s bonds through the cell bars, so I had to re-create all the ‘wall scrawl’ at another angle but in the same places.

All the cell bars etc. were constructed digitally by Rob and placed on another digital layer to enable the characters to be positioned both in front of the background art and also behind/in front of the bars.

There were a few scenes which required concrete walls, so I opted to paint these in sections, scanning at varying levels of finer detail. That way, one piece of artwork could be utilised for various sections without looking identical. I also supplied some vertical struts for added texture. I use the storyboards drawn by the brilliant Adrian Salmon as a basis for each scene, so I know where the art has to be placed in the story.

There is another scene where the Doctor hides from guards. From a tele-snap image, I recreated that frame without any of the characters, where the Doctor hides behind one of the X-shaped wall buttresses, Originally this was an interior scene, however I think it was later placed in the outer edges of the colony. For the sequence where the Doctor talks to the hiding Medok in an alcove, I again painted a modular section of concrete wall and scanned it in stages to form a corridor with slightly varying sections. Then I produced a dark alcove to conceal Medok with boarding timber across the front, complete with wood grain and industrial construction damage scratches.

Medok's cell required several paintings of the same room at different angles. The first features the door, where the Doctor enters the cell. This included the steps down into the cell (which were made taller later on). So there was lots of wall texture required for this one. I decided to go for a traditional rough block wall to add to the bleakness of the room, with lots of lovely texture in the blocks.

The door was painted separately as well, to enable it to be easily cut out and animate it opening. I went initially for a wall entry/communicator panel system for security, as it’s a future colony, however as this was for a programme from the 1960s, the script required a traditional key entry system, so this was added to the image.

For the viewpoint showing the bench in the cell where the Doctor sits, I added a barred window for interest, as well as a few messages scratched into the wall by former inmates. We then realised I had to paint the same image from a different angle for when the Doctor kneels down to free Medok’s bonds through the cell bars, so I had to re-create all the ‘wall scrawl’ at another angle but in the same places.

All the cell bars etc. were constructed digitally by Rob and placed on another digital layer to enable the characters to be positioned both in front of the background art and also behind/in front of the bars.

There were a few scenes which required concrete walls, so I opted to paint these in sections, scanning at varying levels of finer detail. That way, one piece of artwork could be utilised for various sections without looking identical. I also supplied some vertical struts for added texture. I use the storyboards drawn by the brilliant Adrian Salmon as a basis for each scene, so I know where the art has to be placed in the story.

There is another scene where the Doctor hides from guards. From a tele-snap image, I recreated that frame without any of the characters, where the Doctor hides behind one of the X-shaped wall buttresses, Originally this was an interior scene, however I think it was later placed in the outer edges of the colony. For the sequence where the Doctor talks to the hiding Medok in an alcove, I again painted a modular section of concrete wall and scanned it in stages to form a corridor with slightly varying sections. Then I produced a dark alcove to conceal Medok with boarding timber across the front, complete with wood grain and industrial construction damage scratches.

The mines were approached in a collaborative way for their construction, as Rob had been working on the rock wall texture (I think for the ‘teaser-trailer’). Instead of full paintings, I was asked to supply elements for the bracing pillars/mine supports. I painted some timber sections for Rob to wrap, to form the supports as well as some extra digital detail as this was an old abandoned mine, with old nails and lichen/moss on layers in various patterns, which I don’t think were used in the end. I also produced some black line drawn cobwebs to be flipped to negative and animated and supplied the mine cart in which Jamie hides from the Macra. This again was drawn and painted from Adrian Salmon’s storyboard design, with a couple of alterations, then cut out digitally.

After Jamie escapes the Macra in the old mine, he prises some boarding off an opening, to reveal an old cage-lift in which he escapes. For this I was asked to think of the one in The Green Death (1973), so I based my lift on that, adding a lot more interior cage detail with a thin strut construction.

After Jamie escapes the Macra in the old mine, he prises some boarding off an opening, to reveal an old cage-lift in which he escapes. For this I was asked to think of the one in The Green Death (1973), so I based my lift on that, adding a lot more interior cage detail with a thin strut construction.

I think my final work on the story was for the attack sequence, where Ben and Polly are menaced by the Macra outside. My first scene required me to mimic the wonderful Graham Bleatham’s colony modular exterior, where the units had never been completed. In the storyboard, Ben and Polly are standing in front of a partially boarded window, where a large rock in the distance rises up to reveal it to be one of the parasitic crab creatures. This I painted from the angle as shown in the storyboard with the colony wall in the background as well as the night sky, but I think it ended up being cut.

• CHARLES NORTON:

With Graham and Colin handling most of the interior scenes, it still left a few other locations outstanding - the wafting fronds of grass and mottled sand of the wasteland in Episode 1 for instance. Also, the exterior sides of a Police Box needed creating too, for the outside of the TARDIS. The TARDIS, of course, has appeared in other Doctor Who animations, but we didn't want to re-use anything from our back catalogue, as the Police Box prop looked a little different in The Macra Terror compared to how it later looked in Shada.

For these last few background elements, I brought in Lydia Butz. Lydia had done a lovely pencil and charcoal cover of Shada for us back in 2017, which tragically ended up being vetoed and never used. She's also worked pretty extensively in the animation industry and I knew that she'd give us some really nice elements to work with on the planet's surface.

With Graham and Colin handling most of the interior scenes, it still left a few other locations outstanding - the wafting fronds of grass and mottled sand of the wasteland in Episode 1 for instance. Also, the exterior sides of a Police Box needed creating too, for the outside of the TARDIS. The TARDIS, of course, has appeared in other Doctor Who animations, but we didn't want to re-use anything from our back catalogue, as the Police Box prop looked a little different in The Macra Terror compared to how it later looked in Shada.

For these last few background elements, I brought in Lydia Butz. Lydia had done a lovely pencil and charcoal cover of Shada for us back in 2017, which tragically ended up being vetoed and never used. She's also worked pretty extensively in the animation industry and I knew that she'd give us some really nice elements to work with on the planet's surface.